By: Alessandro Spada.

Introduction

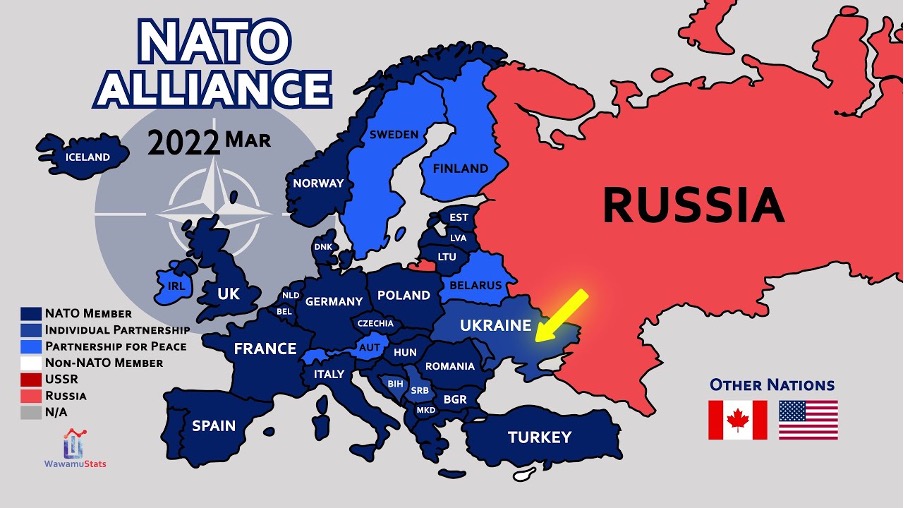

Today, the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (Nato) is an intergovernmental military alliance among the US, Canada and 28 European countries – but it has not always been this large. Indeed, when Nato was first conceived in 1949 it was made up of just 12 members: Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Iceland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, the UK and the US. The creation of the Alliance pursued three essential purposes: “deterring Soviet expansionism, forbidding the revival of nationalist militarism in Europe through a strong North American presence on the continent, and encouraging European political integration”. The accession process is regulated by Article 10 of the Treaty and other European Countries can be invited to participate. The aspiring member countries must meet key requirements and implement a multi-step process including political, economic, defence, resource, security and legal aspects. In case they are experiencing any issue, they can request assistance, practical support and the advice by a NATO programme, which is called the Membership Action Plan (MAP).

Past enlargements

After the end of the Cold War, we can witness four different waves of NATO expansion to Eastern Europe. The first important wave of expansion to the East was launched by the reunification of Germany in 1990. On 12th September 1990, the Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany, commonly known as Two Plus Four Treaty, was signed by the foreign ministers of the Federal Republic of Germany, the GDR, France, Russia, the UK and the USA. The Treaty regulated all the foreign policy aspects of German reunification, including the membership to Nato, and imposed the withdrawal of all the foreign troops and the deployment of their nuclear weapons from the former East Germany and also the prohibition to West Germany’s possession of nuclear, chemical and biological weapons. On October 3rd 1990, the German Democratic Republic and Federal Republic were reunited again.

As to the second wave, the new member countries were Poland, the Czech Republic and Hungary. First, on 15th February 1991 they formed the Visegrad Group. Then, on 1st January 1993, Czechoslovakia split into two independent countries: Czech Republic and Slovakia. In 1997, Poland, Czech Republic and Hungary took part in the Alliance’s Madrid Summit and on 12th March 1999, the three former Warsaw Pact members joined NATO. The main reasons were: “to ensure thecountry’s external security”, to impede “the possibility of a great war in unstable Central Europe” and for Poland also “to advance its military capabilities”.

In May 2000, a group of NATO candidate countries created the Vilnius Group (Albania, Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia). The Vilnius Group resorted to the Membership Action Plan which was introduced by NATO for the first time at the 1999 Washington Summit. In addition, Croatia joined the Vilnius Group in May 2001. The Summit of the NATO Aspirant countries “Riga 2002: The Bridge to Prague” started the path towards the alliance’s membership which took place in Riga, Latvia, on July 5-6, 2002, where the leaders of NATO member and aspirant countries gathered for the last time before the NATO 2002 Prague Summit in November. On 29th March 2004, the largest wave of enlargement in alliance history materialized, except for Albania and Croatia. For Baltic states and Bulgaria, NATO membership symbolized their wish to be part of the European family. NATO was perceived not just merely as a military alliance with security guarantees under Article 5, but as a symbol of higher development, where Baltic states could find their proper place. Moreover, it was the attempt to escape Russian influence, in favor of the protection provided by the American strategic nuclear umbrella and a collective defence.

The same path of the Vilnius Group was followed by the Adriatic Charter of European countries. The Adriatic Charter was created in Tirana on 2nd May by Albania, Croatia and Macedonia and USA for the purpose to obtain their North Atlantic Alliance admission. Albania and Macedonia were previous participants of MAP since its creation in 1999, while Croatia joined in 2002. Moreover, Macedonia also took part in Nato's Partnership for Peace (PfP) in 1995. On 1st April 2009, the North Atlantic Alliance officially annexed Albania and Croatia after their participation in the 2008 Bucharest Summit. Macedonia accession was postponed because of a dispute on the formal name with Greece. Macedonia became NATO's 30th country on 27th March 2020. Montenegro emulated the same path of the latter, but joined three years before on 5th June 2017, after the Accession Protocol signature in May 2016. For Montenegro itself, the major incentives to join NATO were the future eventuality of EU membership, the highest prestige of the Atlantic Alliance and to achieve “Nato’s security guarantee”.

Future enlargements

Bosnia Herzegovina is the only potential candidate which joined the Membership Action Plan on 5th December 2018. In spite of Georgia and Ukraine expressing the will to start their path to the North Atlantic Alliance, their situation is still uncertain. The primary reason remains the need to meet all necessary requirements through important reforms focused on key areas; and, the current Russia-Ukraine war.

Consequences for the European Security

On one hand, many consequences, which were the main reasons for NATO expansion to the East, materialized in reality. For example, the inclusion of Eastern Europe nations in the military agreement have promoted democratic reform and stability there, provided stronger collective defense and an improved ability to address new security concerns, improved relations among the Eastern and Central European states, fostered a more stable climate for economic reform, trade, and foreign investment, and finally, improved NATO's ability to operate as a cooperative security organization with broad European security concern,” as stated in the clear purposes contained in a prepared statement of the Secretary of State Madeleine K. Albright on 23rd April 1997.

On the other hand, in spite of NATO's open door policy with Russia, the latter constitutes the largest threat for European security once again in the energy, political and military field. Indeed, the current conflict in Ukraine shows the evident ambition to create a new Russian empire by the Russian President, Vladimir Putin. Many warnings about Russia’s reaction were expressed in the declarations of Biden’s CIA director, William J. Burns, when he worked as counselor for political affairs at the US embassy in Moscow in 1995. On 26th June 1997, a group of 50 prominent foreign policy experts that included former senators, retired military officers, diplomats and academicians, sent an open letter to President Clinton outlining their opposition to NATO expansion”. In the end, the father of the Cold War containment doctrine, George F. Kennan described the NATO expansion as a “tragic mistake”.

Conclusion

The current Russian invasion in Ukraine puts in clear evidence the necessity for the EU countries to accelerate the formation process of the European Army. They will have to achieve energy independence by using Russian gas, diversifying their own supplier countries and to invest massively in the green economy. Moreover, the EU must strengthen its common foreign policy, implementing an effective diplomatic action and speaking with one voice to cope with the great tensions around Europe and the rest of the world. If not, the European project will risk crumbling.