Author: Giovanni Giacalone.

On the morning of May 10th Paraguay’s anti-drug prosecutor Marcelo Pecci was murdered by two hitmen on a jet ski who reached the beach where he was vacationing with his wife and shot him in the head and the back. The murder took place in Barù, a renowned location just 45 minutes away from the city of Cartagena, Colombia. The jet ski was rented by the killers in Playa Blanca, approximately 3 km away from the resort where Pecci and his wife were staying.

“One of the men got out and without saying a word he shot Marcelo twice, one shot hit him in the face and another in the back,” Pecci’s wife, Claudia Aguilera, told the newspaper El Tiempo. The hitmen then fled in the same jet ski. A hotel security guard was also shot at, although he was not injured. Prosecutor Pecci was traveling without bodyguards and his wife said that they had not received any type of threat. Additionally, the Colombian police forces were not aware of his presence in the country.

The couple had traveled from Paraguay to Cartagena on May 5th to spend their honeymoon there. The following day, after a quick visit to the city’s historic center, they reached the Decameron Hotel and Resort in Barù, where they planned to spend the rest of the time before heading back to Paraguay on May 10th, as indicated by the message published on Monday May 9th by Aguilera on social media: “The last sunset in Barú, but we will have millions more together.” At approximately 10:30 am on Tuesday morning, the last day of vacation, Pecci was gunned down in front of his wife and tourists at the hotel’s private beach. A group of Paraguayan tourists who were at the same hotel as Pecci and were leaving on the same day complained that they were held for questioning by the Colombian police for hours, and added that at the hotel and resort there was no visible security, as reported by ABC TV Paraguay.

Marcelo Pecci was a high-level prosecutor who specialized in contrasting drug trafficking, money laundering and organized crime. He had recently participated in the operation Ultranza Py against drug trafficking in Paraguay and he was also investigating the infiltration of Ndrangheta in the country. According to Gen. Jorge Luis Vargas, head of Colombia's national police, Pecci was the victim of "transnational" criminals working across borders and the murder was very likely highly planned, with a large amount of money spent to carry it out. He also added that narcos or even international terrorists could be behind the murder.

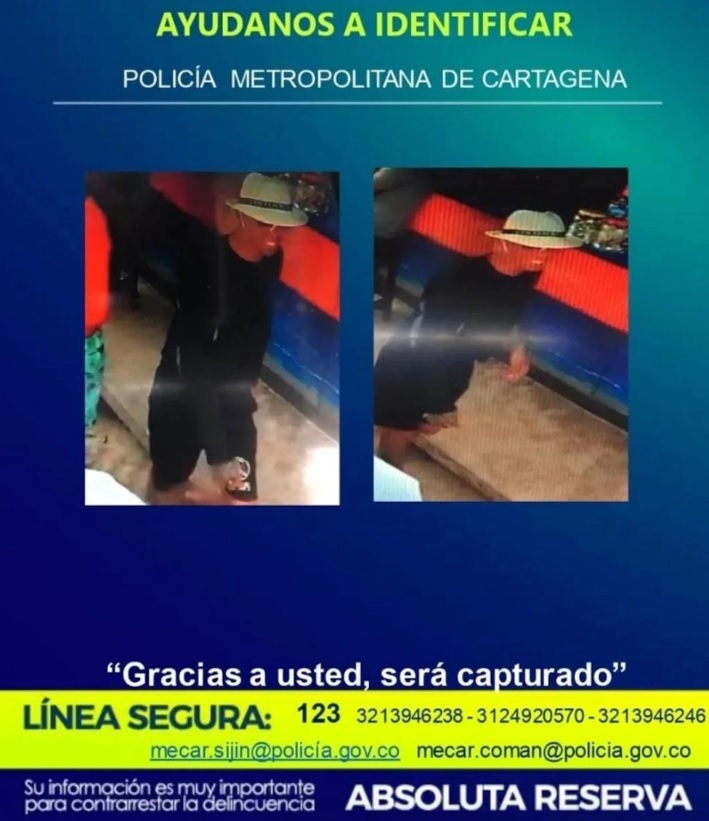

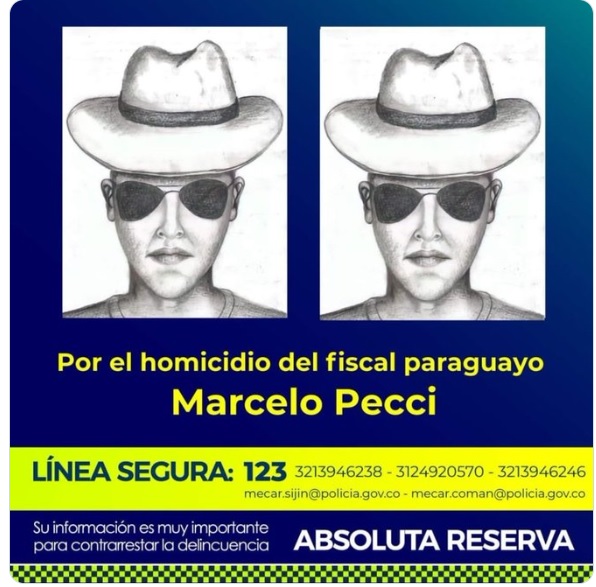

On the same day of the homicide, the Colombian police released a picture of one of the two alleged killers, a man dressed in black, wearing a Panama hat, with a Caribbean accent. The Colombian authorities announced a reward of up to 500 million Colombian pesos ($12,000) to anyone who can provide information about the assassins. The owner of the jet ski that was rented to the two hitmen said that they paid $50 to use the vehicle for 30 minutes, but they returned it just 15 minutes later.

There are currently two versions regarding the killers, one is that they followed Pecci and his wife all the way from Paraguay to Barù, traveling on the same plane; the second one is that they were contracted in Cartagena to conduct the hit. Rocio Vallejo, a member of the Paraguayan Parliament and the Patria Querida party claimed that organized crime is behind it, she pointed the finger against the “narco-politica” and even accused some Parliament members of being linked to the narcos, adding that “narcotrafficking knows no borders”.

As explained to the ITSS by the Brazil-based investigative journalist Maria Zuppello, who is specialized in organized crime and terrorism in Latin America: “The murder of Pecci is a tragic page not only for Paraguay but for all of Latin America that lost a prosecutor of great value. The various leads that are being followed range from the terrorist matrix of Hezbollah to the former president of Paraguay, Horacio Cartes, who was already targeted by the Dea for money laundering and narco-activity in the United States. It is now clear how Latin America has become a privileged hub for narco-terrorism”. Following the murder, the Paraguayan police searched the prison cell of Lebanese narcotrafficker Kassem Mohammed Hijazi, who was arrested in August of 2021in Ciudad del Este thanks to an investigation led by Pecci with the support of the Dea. In the meantime, Noticias Caracol revealed that four Paraguayan women who had arrived on the same flight and were staying at the same hotel as Pecci, and a person considered very close to the murdered prosecutor, are under the radar of the Colombian authorities.

It is unclear why Pecci, considering his high-level profile, was traveling without bodyguards and had not warned Colombian authorities about his presence there. It is possible that since he hadn’t received any threat, as claimed by his wife Claudia Alvarez, he thought that he would be safe in a place like Barù, renowned for international tourism and with a very low crime rate if compared to other parts of Colombia; however, the killer were after him. The investigations are currently underway with the help of the Dea, the Fbi, Interpol, and it is plausible that there will be news in the upcoming days.