Authors: Maria Makurat (Cyber Security and AI Team) and Anurag Mishra (USA Team)

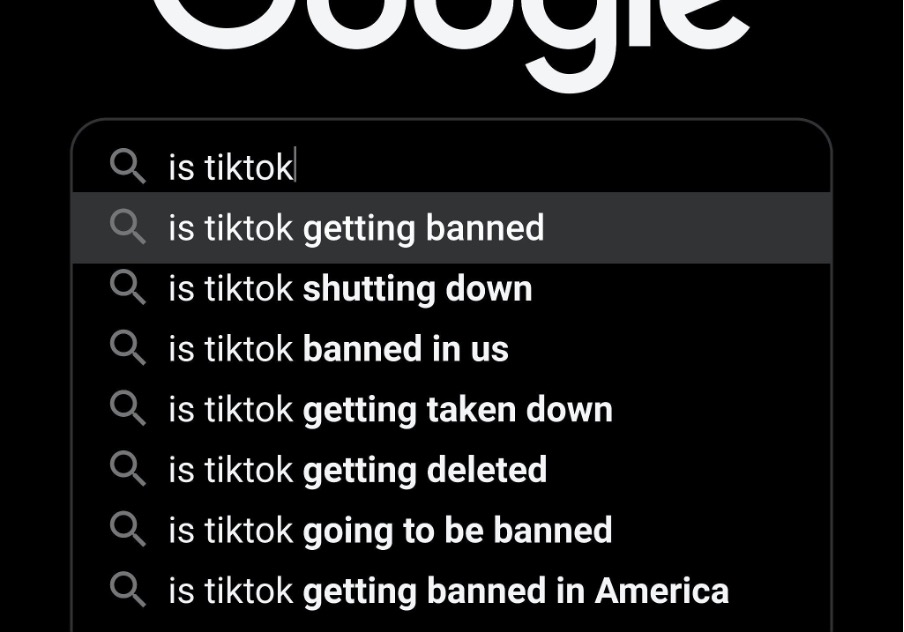

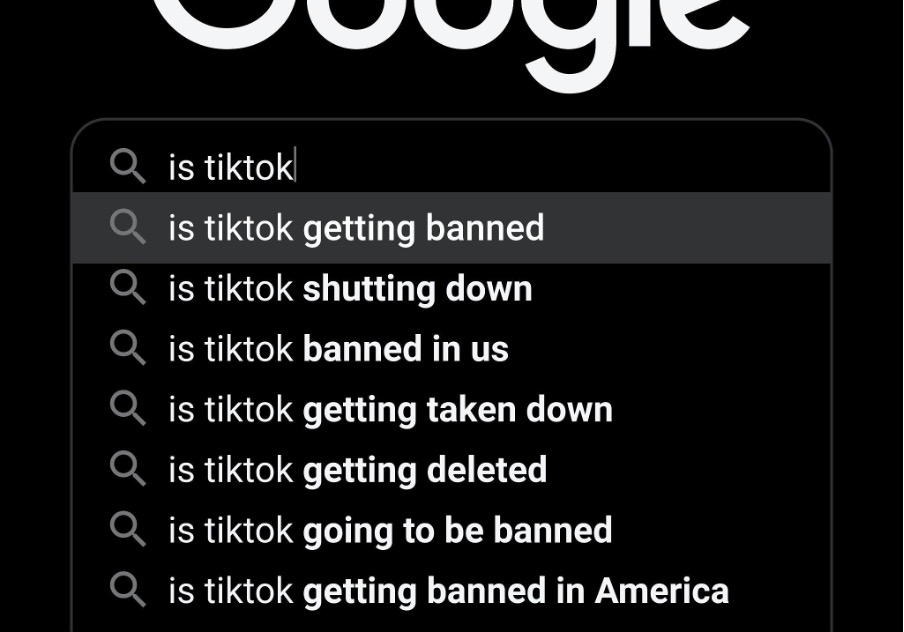

TikTok and the “Ban Hammer”

The debate of apps such as TikTok being a security threat to individuals as well as countries has been going on for a while. Several articles, studies and other blog articles have been, and are still being released on this hot topic. One of the main concerns remains: TikTok is collecting data of users against their consent whilst one is also not using the app. Since TikTok is owned by ByteDance, a Chinese-owned company, many Western countries and especially the US are highly sceptical and states such as Montana have even taken the initiative to ban the app altogether. What does this mean for cyber as well as cultural security issues? Many factors and international events surround this debate such as TikTok already being banned in India, the issues of the Chinese state being seen as a spy and whether one can see TikTok as a surveillance weapon? Cyber security as well as cultural issues tie into the debate where we see theories of whether we have a “cyber war” in relation to social media platforms as well as cultural matters if TikTok is having a negative impact on countries. This article explores the issues highlighted above and opens up possible questions that still need to be asked.

Montana Mounts a “Blackout Challenge” to TikTok

Senate Bill #149 of the 68th legislature of Montana, which was introduced by state senator Shelley Vance makes the offering of the app on any application store illegal and prescribes a fine of $10,000 per day for each time someone accesses TikTok, “is offered the ability” to access it, or downloads it. Governor Greg Gianforte, a Republican from Montana, had approved the law on anticipating potential legal challenges. Although the law is not set to be enforced until January 1, 2024, there are doubts about the state's ability to implement it effectively. The impact of this new legislation in Montana is expected to be more significant than the existing TikTok bans already implemented on government devices in approximately half of the states and at the federal level in the United States.

From the outside, the one-of-a-kind ban looks like an assault on ByteDance’s data-gathering exercise but also has a deeper purpose of extinguishing the app’s ability to influence the impressionable youth of America.

One of the major reasons why TikTok became the conservative eyesore and a major cause of worry for parents was the “Blackout Challenge.” Also known as the "choking challenge" or the "pass-out challenge," it involved urging individuals to hold their breath until they lose consciousness as a result of insufficient oxygen. While the Blackout Challenge was the biggest troubling online challenge, causing as many as 20 children to lose their lives, a slew of similar troubling trends made TikTok infamous. "Dry-scooping," climbing on tall stacks of milk crates, removing your own IUD, and eating massive amounts of frozen honey and corn syrup, and the list goes on.

The problem with TikTok does not end there. When juxtaposed with the wider scheme of things, TikTok appears to be one of the many arrows in the Chinese quiver. The issue of Chinese Police Stations coming up on the United States’ territory has landed many in the stew and has made the American government restive. Taking a leaf out of India and some European countries’ books, several states in the US decided to ban TikTok on office/government-issued phones and devices. As of April, 34 American states have banned TikTok on government-issued devices. The idea behind banning the mischievous app has largely been to secure any data leaks. India was the first country to ban TikTok and several other Chinese mobile applications nationwide, citing national security concerns. India banned TikTok as early as June 2020. At first, the ban was seen as a mild yet conclusive response to the PLA’s misadventure across the Sino-Indian border, but as more countries put restraints on the Chinese app, the Indian government’s official position on the ban seems to have been vindicated.

Reservations and concerns abound TikTok and have only gone on to grow in the past three years. Not just the adversaries and rivals but even allies like Pakistan and North Korea have blocked TikTok. The question nevertheless remains whether TikTok is just an online pastime or a phisher.

Weapon of Mass Surveillance: TikTok and its Cyber Security Issues?

The debate surrounding TikTok being a security issue has been around for a while. Several individuals as well as companies had their doubts but as of around April 2023, one has been seeing a surge in states and countries being serious about banning the popular app. The major concern lies within the fact that TikTok is owned by a Chinese company and several discrepancies have arisen concerning the security of the app. It is being repeatedly “expressed that TikTok and its parent company, ByteDance, may put sensitive user data, like location information, into the hands of the Chinese government.” This together with political tensions between Russia, China and the West in relation to the Ukraine war add to the TikTok debate with companies being concerned that data is being stolen. Countries find themselves recently in much more complicated relations.

One can link this to traditional international affairs theories such as whether we will even have a “cyber war” (discussion by Thomas Rid) and how social media is being “weaponized” (discussed by P.W. singer, Emerson T. Brooking and Dr Andreas Krieg). “In so doing, social media has evolved from a mere distraction machine into a tool of sociopolitical power, galvanising public awareness and civil-societal activism.” It is being discussed that ever since the 2016 elections in the US with Russian interference, that other social media platforms, where TikTok can possibly also be an instrument, can be used to spread false information and not only be used as a tool by itself to collect data. Countries such as Germanyalso increasingly see the issue of social media platforms being used to spread false information as well as collecting data (BIS: Bundesamt für Sicherheit in der Informationstechnik). The so-called “Digitalbarometer 2020” released by the BIS, stated that in Germany for the year 2020, every fourth individual was affected by some type of cyber-attack and every third was affected financially. Whilst Germany has not released a law that forbids the use of TikTok, it is being discussed by the Federal Minister of the Interior and Community that one needs to stay alert and be aware of the possible consequences.

This issue is also being discussed very intensely by scholars such as Dr Andreas Krieg (recent work “Subversion - The strategic weaponization of narratives”) and Dr Kathleen Hall Jamieson (Cyber-War : How Russian Hackers and Trolls Helped Elect a President). We see both now in the international affairs academic world as well as the communications and cultural disciplines a debate, on how social media platforms are being weaponized (see also this blog article on hate speech on social media). Now perhaps more than ever, interdisciplinary communication between different academic strands is needed to address the issue. So we see it is not only the issue of TikTok being owned by a Chinese company and the possible spread of false information but also the physical issue of collecting data. We have both cultural/ethical and cyber security issues.

To Ban, or Not to Ban?

To mitigate the goodwill loss and the loss of business that TikTok has encountered, it would be wise for the company to make itself more transparent and even sell stakes, as beseeched by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the U.S. The company will also need to come clean on the accusations of data theft and spying. The root of all remains the involvement of the Chinese state in its corporate entities and in the long run, such involvement will not go unnoticed by the countries hosting Chinese businesses. When considering all these factors, open questions remain such as if we will see other countries following suit in banning TikTok and how likely is it that more organisations will take action? Do we see a certain cyber war taking place in the realm of social media or is it more an issue of moral and ethical values? Younger generations still use TikTok in their daily life, especially since this is also linked to businesses (such as Infleuncers as well as big companies) which could prove problematic in the future. Perhaps stronger rules are required that regulate the use of TikTok and its data collection if the app is to be further used. It remains to be seen how this develops and whether individuals will be concerned with the use of the app.